The fundamental misunderstanding in Team Topologies

Mastodon Thread

Patricia Aas, 24 May 2025

This blogpost is a barely edited version of the Mastodon thread 1 on Team Topologies. It was written over the span of 9 days as I was reading the book for the second time, so this is not something written up after. (I wrote a thread the first time I read it too 2) It is what it is. I wrote Mastodon threads because I really couldn’t read it otherwise, the book has no narrative, is extremely repetitive and is mostly just regurgitating what I refer to as Other People’s Thoughts, which you could read better in the original authors work (as you should because their work is often quite misrepresented). Their actual Original Thoughts are in my opinion extremely harmful, and that is basically what this thread goes into. The talk I was preparing was presented at NDC Oslo in May of 2025 and will come on their YouTube channel. The slide-set for the talk I was making is here 3.

Thread Introduction

Alright, I’m back with what I assume will be a week long rage thread about a book I hate. It’s really not important for current events in any way, but I signed up for a talk about it in the before-times. So mute this, it’s absolutely not interesting unless your org is actually reorging based on this book. I’d suggest not to argue with me in this thread, I’ve bought the book twice and I hate it. I have paid my dues, and I am already pissed that Past Patricia made me read it again.

Reasons I hate the book

- It’s wrong. If you follow whatever you manage to actually glean from this book your org will be less efficient and worse in basically every respect for absolutely no good reason.

- It is really, really badly written.

- The “logical” argument does not follow actual rules of logic (which I find surprisingly infuriating).

- The parts that are not garbage are just regurgitation of other peoples thoughts.

Since people tell me that I’m supposed to say something nice too: The graphical designer did a really great job, y’all should hire him, his name is Devon Smith. The editors also did ok, the titles of parts, chapters etc almost seem to make sense.

Last time I yelled at this book

Thread 4 from the first time I read this book.

Fundamental “logical” conclusion of the book

To force an organization to produce micro services (the epitome of software development) and not to risk a monolith (because those are the only two options that exist to man) one must create an organization that mimics micro services by eliminating as much cross team communication as humanly possible.

An organization that cannot communicate is the optimal organization.

Such an “optimal” organization consists of teams full of drones that do what they’re told, have no need to understand the broader context in which they exist, and that don’t have the “cognitive overload” of integrating that context into their work. They will NOT (unless carefully orchestrated) communicate with anyone outside their bubble.

This is optimal because reasons.

It is a made up intellectual exercise that undermines decades of proven progress in software development, creating countless silos with all the associated problems. It is anti-agile, anti-devops, anti everything, and they don’t even realize.

The rest of the book is other people’s work.

Any part of it you might agree with is someone else’s idea. They are pulling in the works of literally dozens and dozens of other peoples original work. Some of it is contradictory to each other.

- Everything written about software dev in the past 25-45 years is in there somewhere.

- That does not make it good.

- That makes it unreadable.

Meta

FYI any “well actually” might result in a mute or a block because (read post 1) I’m not in the mood. I literally paid actual money for this book (twice) so I consider that to be all the dues I’m required to pay to say why I hate it.

Part I: “Teams as the means of delivery”

Chapter 1: “The Problem with Org Charts”

Starting from the beginning. The logical foundation from which all this springs: Part 1, chapter 1. Based around 2 ideas belonging to other people:

- Conway’s Law, 1967 (which is an observation based on Mel Conway’s own experience) 5

- Inverse Conway Maneuver, 2015 (which is a made up thought experiment by James Lewis et al of Thoughtworks) 6

Conway’s law, an observation

Based on my own experience I can see how Conway’s Law can be plausible:

”[O]rganizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.” Melvin E. Conway, How Do Committees Invent? 7

Agile and DevOps was about more communication

In many ways this was the problem that agile and devops tried to solve: that constraints on communication with our users and customers (agile) and between dev teams and ops teams (devops), created processes that resulted in inferior products and experiences (agile), and systems that were hard to maintain and change (devops).

The solution in both agile and devops was one of closer collaboration.

The problem agile was trying to solve was one in which we tried to design everything up front and then had some sort of final delivery often years later, with few sync points in between, and often resulting in systems that might formally fulfil the requirements, but was often universally hated and often discarded or the basis of long legal battles.

The problem devops was trying to solve was imo a result of a culture clash between ops and dev where they are measured on fundamentally different metrics. Ops on stability and security, dev on feature development. One is awarded for keeping things the same, the other for changing things.

DevOps was therefore fundamentally a cultural project, and its success can be seen in the fact that most juniors have no idea what I’m talking about.

Inverse Conway Maneuver, a thought experiment

So to Inverse Conway Maneuver, this is a thought experiment, not based on experience. The basic idea is as follows:

“evolving your team and organizational structure to promote your desired architecture” 6

The reasoning here is that if we make an organization whose “communication structures” (to use Conway’s words) reflect the architecture we want to achieve then Conway’s Law will make this organization produce a system with this architecture.

Fundamentally: Re-org your organization to reflect the architecture you want.

Formal logic argument

This makes a bunch of fundamental assumptions that should be examined, first of all logic:

- In formal logic we have “Modus ponens” 8 typically of a form like: “If it rains the grass gets wet, it has rained, therefore the grass is wet”

- Another related concept is “Modus tollens” 9, which would then be: If it rains then the grass gets wet, the grass is not wet therefore it did not rain.

- Associated with these is a common fallacy “Affirming the consequent” 10 which in this example would be: If it rains the grass gets wet, the grass is wet, therefore it has rained. This fallacy is in this case easy to refute, we don’t know why the grass is wet, it might have been sprinklers that got turned on.

Modus ponens

To scientifically prove Conway’s Law is difficult/impossible, we would need to formally define a whole host of things (including, most importantly, what “communication structures” are), and then we would need to find appropriate measurements and run a bunch of experiments. But for this entire thread I will assume that Conway’s Law describes a real mechanism in tech organisations: Two groups of people that do not collaborate, but create software that needs to collaborate, will tend to create at least two modules (at minimum one each) and create some form of communication between them: ones output is the others input (possibly bidirectional), for example an API or similar.

I also firmly believe that this is the nature of the fundamental problems that both agile and devops tried to tackle: How to better collaborate across organisational boundaries to create better systems faster.

Conway’s Law as formal logic statement

So in formal logic what is Conway’s Law saying?

I think it is fair to boil it down to this:

If two groups can’t effectively collaborate (P), they will create an interface (Q).

Or in Modus Ponens:

If P, then Q.

P.

Therefore, Q.

In Modus Tollens:

If P, then Q.

Not Q.

Therefore, not P.

So according to Modus Tollens (if we assume Conway’s Law) if two teams manage to create a cohesive system then they have found a way to collaborate.

Fallacy Affirming the Consequent

The fallacy Affirming the Consequent has the form:

If P, then Q.

Q.

Therefore, P.

Inverse Conway Maneuver is a logical fallacy

Inverse Conway Maneuver would then be:

If two groups can’t effectively collaborate (P), they will create an interface (Q).

They have created an interface (Q).

Therefore they can’t effectively collaborate (P).

However, that’s of course not true, there are a million different reasons why you would create an API, I would go so far as to claim that every single programmer creates interfaces in their own code, even when they are only “collaborating” with themselves. We call them many things, one word for them is: Abstractions.

I also claim that a single programmer is peak communication efficiency when it comes to communicating with themselves, more than any other programmer would be with them.

You have direct access to your own memory, you share style, preferences and have a common understanding of the system and its requirements.

Based on the above I will claim that Inverse Conway Maneuver is not a logical consequence of Conway’s Law, but rather a logical fallacy.

If it was necessary to shape organizational “communication structures” to produce the desired interfaces in the architecture, then a single team or a single person would not be able to produce such a system.

Fundamental assumptions:

- Assumption 1. The desired architecture is known

- Assumption 2. The desired architecture is optimal

Inverse Conway Maneuver:

- Assumption 3. The desired architecture can only be achieved by an organization with the same “communication structures” as the desired architecture.

All of these assumptions are problematic, we’ll get back to that later.

Lets phrase it as a statement of logic in terms of Conways’ idea of “communication structures”:

If you shape “communication structures” in your organization to reflect your desired architecture (P), then your system will inevitably have this same communication structure (Q).

According to Modus Tollens:

If P, then Q.

Not Q.

Therefore, not P.

Where !Q is : The system does not reflect the communication structure

Proof by contradiction

If there exists a team or person that can produce a system with an interface (for example an API or one or more collaborating micro services or even a layer of abstraction), then such a team or person would be a violation of Inverse Conway Maneuver, they have produced a system with “communication structures” that are not a reflection of their organizational “communication structure”.

Or if there exists a group of teams that build a system without interfaces, since such a thing does not exist we’ll just call it a monolithic system. Then that is also a violation of such a statement.

Informally

I think the fundamental problem here is that Conway’s Law is descriptive and Inverse Conway Maneuver is normative.

Conway’s Law says that this tends to be true, or more explicitly: It was a pattern Conway himself observed.

Inverse Conway Maneuver is not an observation of actual teams producing actual software, it is a thought experiment mostly concerned with answering a question that has not been asked: How does a reorg affect architecture?

I find it extremely naive and lacking in analysis, hiding decades of academic study of teams in what superficially mimics a logical conclusion, but in fact is extremely easy to refute: A single person can create both a monolith and a micro service architecture.

Conway’s Law fundamentally only says that it is easier to collaborate with people we talk to, which is honestly only a revelation to people in tech.

People who collaborate can create all kinds of architectures, and most of all: they can adapt to changing conditions.

Problems with the Fundamental Assumptions

Which brings us to the problem with the Fundamental Assumptions:

- Assumption 1. The desired architecture is known

- Assumption 2. The desired architecture is optimal

I question both of these, but probably 2 most of all.

We learned a long time ago that upfront design makes bad systems. And these two assumptions are 100% upfront design.

I will claim that we never KNOW which is the optimal architecture.

We have an hypothesis for what is optimal for us, but there are (as opposed to what this book seems to assume) many more architectures than “monolith” and “micro services”.

I would even claim that most systems contain many architectures.

Even the most basic CRUD system has a backend, frontend, data layer, data analysis, maybe a data lake, monitoring, CI/CD, maybe even some machine learning. All of which can be structured in many ways, and interface in many ways.

Then we have embedded systems, browsers, calculator mobile apps, single player games, multiplayer online games, audio mixing applications, video editing software, compilers, operating systems etc etc.

Fundamental assumptions in the book as a whole

This entire book hinges in my opinion on a handful of assumptions:

- There are two architectures: monolith and micro services

- Micro services are vastly superior

- That you can force an organization to create micro services by controlling the way people are allowed to communicate

- That such an organization will be efficient

- That such an organization will make good systems

- That such an organization will be a good place to work

I question all of these assumptions.

Or more directly, I disagree with all of these assumptions.

Team Topology directly contradicts the article Conway’s Law stems from

It’s also important to point out that Conway himself argued, in this paper, the one from which this law is derived, for a flexible organization that can adapt to changing design and geared towards collaboration.

“Conclusion

The basic thesis of this article is that organizations which design systems (in the broad sense used here) are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations. We have seen that this fact has important implications for the management of system design. Primarily, we have found a criterion for the structuring of design organizations: a design effort should be organized according to the need for communication.

This criterion creates problems because the need to communicate at any time depends on the system concept in effect at that time. Because the design which occurs first is almost never the best possible, the prevailing system concept may need to change. Therefore, flexibility of organization is important to effective design. Ways must be found to reward design managers for keeping their organizations lean and flexible.” 11

Other People’s Thoughts

Jeez, we’re still on chapter 1, and we’re not even done with that. If you want to see a specific pattern that is evident throughout the whole book then this chapter is sufficient.

The authors keep referring to other peoples work, seemingly agreeing with absolutely everything and then claiming that TT is 100% in line with all of it. Bringing up other peoples work is fine, great even, but in this kind of book that requires discussing those ideas and how they relate to one’s own contribution. This compare and contrast, discussion and evaluating pros and cons is sorely missing. It means that a good 60-70% of the book is just rearticulating other peoples thoughts without actually analyzing them or contrasting them to each other.

This would be fine for a text book for a university course, as a tour of the field, but this is not such a text book. If you are presenting a thesis: “Team Topologies is good actually”, then you need a better argument then “here are a bunch of people with a wide range of thoughts and what we are doing they would all totally agree with”.

This could’ve been a blog post

I think fundamentally that is my biggest gripe with this book, it completely fails to argue why “TT is good actually”. There is no coherent argument, and it takes a lot of effort to tease out what are their own original thoughts out of the avalanche of Other People’s Thoughts. And that is fundamentally the frustrating part, once you tease out those thoughts from all of the other noise there is hardly anything at all. It seems to be a book length answer to: What if Inverse Conway Maneuver and a decade+ old blog post from Spotify had a baby.

We’ll get back to the blogpost. It is important. It’s somewhere later in the book.

Cognitive Load is bullshit

The final concept in chapter one, which I think is complete bullshit, is “cognitive load”. As always they bring up a bunch of different other people that they use as alibis for their own thoughts, that I will summarise as follows:

A team must be shielded from complexity because their little minds can’t take it.

This is “proven” with someone else’s anecdote which makes zero sense in this context: A team makes a thing which becomes very popular and because of that the workload increases so that they are not able to handle it alone anymore.

Lesson: if you’re successful and your product gets many users and you need to expand the team to service those users the fundamental problem isn’t increased workload, but that your little minds can’t grapple with… something. To be honest the logic makes zero sense.

The argument is garbage, but even if we would accept it I claim that:

- “Shielding” a team from information or context is paternalistic bullshit, they are skilled grownups that can perfectly well discern what is relevant and irrelevant information for their work.

- Hiding information and context from people who build things is Bad Actually, because they might need this information to make the right product, and you as an outsider can’t know what they need to know.

- Talking about a team’s “cognitive load” is ridiculously condescending. These people are grown ass adults, they would probably out IQ you on any test, stop treating them like children it’s insulting.

Finally, it is quite insulting that a team that is being overwhelmed with tasks is referred to as “a bottleneck” instead of saying that they are understaffed. This is a way of shifting blame on to a team that has clearly done great work, because their product is now extremely popular. The fact that they are understaffed is not their fault.

That brings us to the end of chapter 1. On to chapter 2: “Conway’s Law and Why It Matters”

Chapter 2: “Conway’s Law and Why It Matters”

Monoliths Are Bad Actually and Micro Services Are Good Actually

This is where the authors will lay out their claim (sprinkled within a lot of Other People’s Thoughts) that Monoliths Are Bad Actually, and that Micro Services Are Good Actually.

The basic thesis seems to be that since microservices are the ultimate architecture, you should organize your teams as microservices, there should be no common “dependency” between them. And their work product will be (and should be) a micro service.

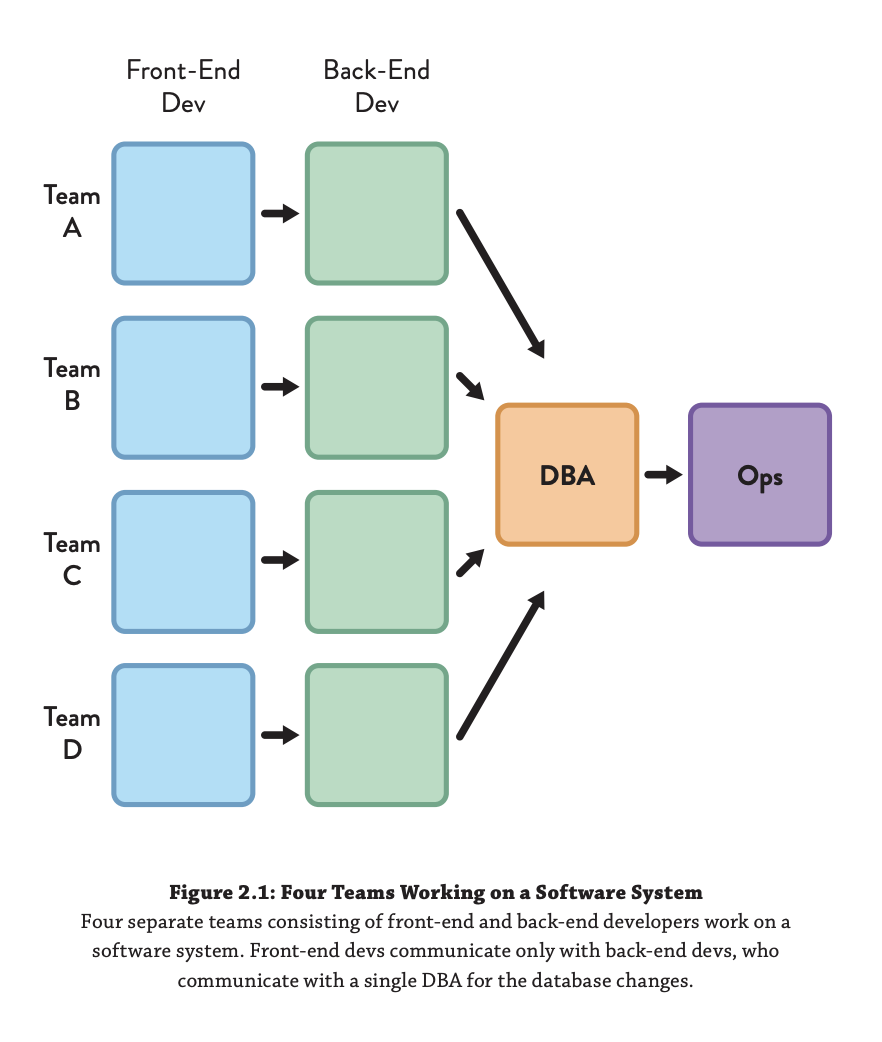

The argument is strange because they spend a lot of time talking about how a shared database is a bad thing and something about DBAs, and then a lot about Cloud Great, but to be honest I haven’t seen a DBA in a decade and all the databases are in the cloud. Also today’s version of a DBA would be a platform engineer and they love those.

They talk about that we have a frontend and a backend because we have frontend and backend teams, and y’all we have a frontend because it runs in the browser and a backend because it runs on the server and that argument is also garbage.

There also seems to be a weird idea that there is some sort of handoff from a backend team to a DBA team and then to an Ops team which is not how any of this works.

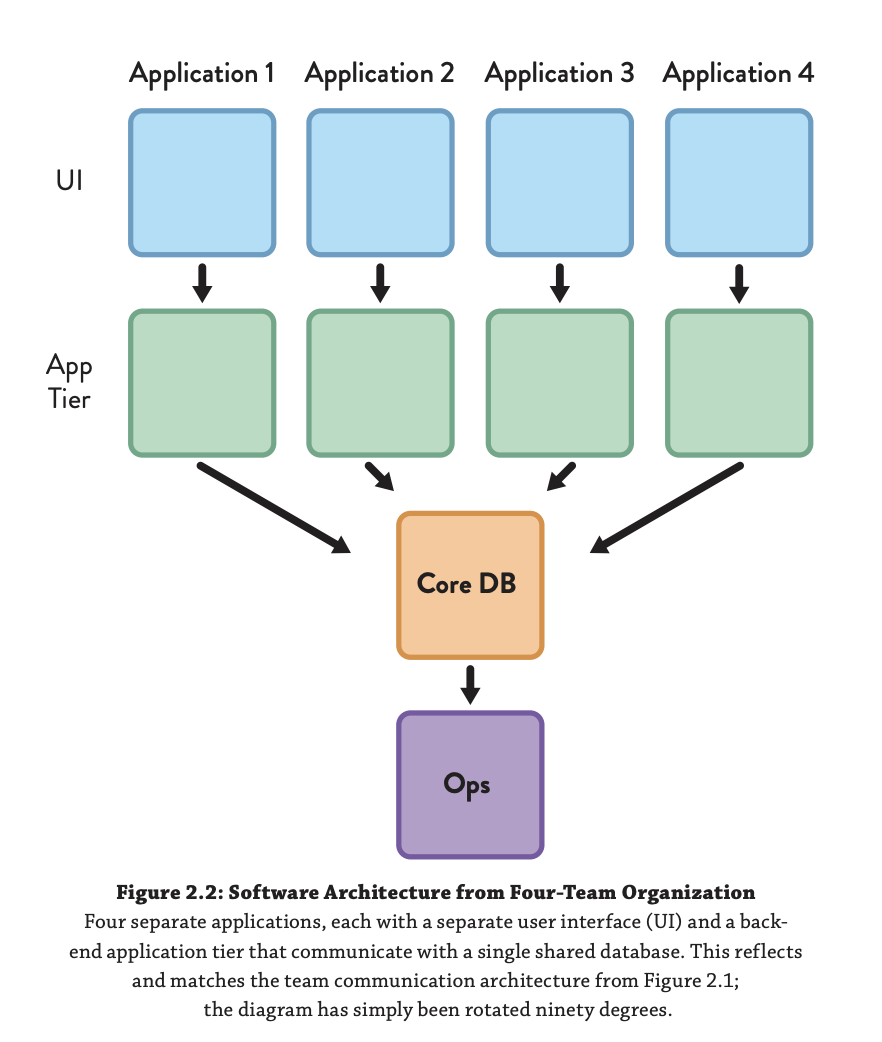

And since I’m honestly worried y’all will think I have completely misunderstood everything, I present a couple of beautiful (told you the graphical designer was good) and completely nonsensical figures from this chapter.

I can only assume that they worked on some Oracle based enterprise project in 2000 or something, because this makes no sense and to be honest I don’t think it makes sense describing an enterprise Oracle based system even then. But I’ve been in the business for 20 years and this is nonsense.

Anyway, whatever this is supposed to be, this is our straw-man, and this is a result of… people talking with each other? Talking with the wrong people? Who even knows.

Restricting communication to force a design

They explicitly talk about using Conway’s comment about people who can’t talk, can’t collaborate, and how they can use that to stop unwanted communication. Screenshot in next post.

Galaxy Brain: if they can’t talk, they can’t collaborate!

It’s almost funny how they draw the exact opposite conclusion from what Conway was expressing. He was expressing a problem, they have written a whole book on creating this problem on purpose.

Picture of parts of a page in the book:

“Why are organizations unlikely to discover or sustain certain architectures? Conway provides some clues in his 1968 article: “Given any [particular] team organization, there is a class of design alternatives which cannot be effectively pursued by such an organization because the necessary communication paths do not exist.”

Communication paths (along formal reporting lines or not) within an organization effectively restrict the kinds of solutions that the organization can devise. But we can use this to our strategic advantage. If we want to discourage certain kinds of designs - perhaps those that are too focused on technical internals - we can reshape the organization to avoid this. Similarly, if we want our organization to discover and adopt certain designs - perhaps those more amenable to flow - then we can reshape the organization to help make that happen. There is, of course, no guarantee that the organization will find and use the designs we want, but at least by shaping the communication paths, we are making it more likely.

Organization design using Conway’s law becomes a key strategic activity that can greatly accelerate the discovery of effective software designs and help avoid those less effective. (In Chapter 8, we go into more detail on how to evolve an organization strategically with Conway’s law in mind.)”

DevOps: We have a communication wall between Dev and Ops, we should tear it down!

Team Topologies: What if, hear me out, we build walls everywhere!!! Hashtag winning!!!

That snippet brings up a new term “flow” which they use a lot. I don’t think they properly define it anywhere, but my current understanding is that it means “we can do stuff without talking to or coordinating with anyone else”.

This is in my experience an illusion, but whatever, it’s fine. It is a bit annoying that the term “flow” actually has a meaning in programming in particular, and deep work in general, but who am I, the word police?

Narrator: Well, actually, Patricia…

Misrepresenting Conway

They also constantly misrepresent what Conway said which is annoying me to no end.

Example:

Conway:

“Because the design which occurs first is almost never the best possible, the prevailing system concept may need to change. Therefore, flexibility of organization is important to effective design.”

TT:

“Conway’s law tells us that we need to understand what software architecture is needed *before [their emphasis] we organize our teams”*

I told y’all to mute this thread, we’re only on day two, chapter two of eight. You can still mute. Just sayn’.

Chapter 2 has a sub header that says the quiet part out loud right in the title:

“Restrict Unnecessary Communication”

That’s what this book should’ve been called, because that is what this book is about.

To be honest, that whole subsection is critical for understanding their entire world view. See next post for pictures.

Then we will discuss the reasons why this is problematic.

I have so many issues with this text we’ll just have to take them one by one. As a meta comment I am concerned that the authors are once again taking Other Peoples Thoughts and presenting them as if they’re saying the opposite of what they were actually saying, but I’ll have to get back to that later (only so many digressions at a time).

“Restrict Unnecessary Communication

One key implication of Conway’s law is that not all communication and collaboration is good. Thus it is important to define “team interfaces” to set expectations around what kind of work requires strong collaboration and what doesn’t. Many organizations assume that more communication is always better, but this is not really the case. What we need is focused communication between specific teams. We need to look for unexpected communication and address the cause; as Manuel Sosa and colleagues found in their 2004 research into aircraft manufacturing, “managers should focus their efforts on understanding the causes of unaddressed design interfaces… and unpredicted team interactions… across modular systems.”

Mike Cohn, one of the originators of the Scrum product-development approach, asks these questions to assess the health of inter-team communication within an organization: “Does the structure minimize the number of communication paths between teams?… Does the structure encourage teams to communicate who wouldn’t otherwise do so?”

Here, Cohn is addressing the need to ensure that if, logically, two teams shouldn’t need to communicate based on the software architecture design, then something must be wrong if the teams are communicating. Is the API not good enough? Is the platform not suitable? Is a component missing? If we can achieve low-bandwidth communication - or even zero-bandwidth communication - between teams and still build and release software in a safe, effective, rapid way, then we should. This is visualized in Figure 2.5, which is based on Henrik Kniberg’s “Real Life Agile Scaling.”

Figure 2.5: Inter-Team Communication

Communication within teams is high bandwidth. Communication between two “paired” teams can be mid bandwidth. Communication between most teams should be low bandwidth.

A simple way to restrict communication is to move two teams to different parts of the office, different floors, or even different buildings. If the teams are virtual or mostly communicate over a chat messenger tool, the volume and patterns of the team-to-team communications can help identify communications that do not match the interactions expected for the software architecture.

Similarly, if a large team regularly deals with two separate areas of the system, it can be useful to split this team into two smaller teams dedicated to each part, although only if it’s the same team members who work on different systems. If the whole team works on more than one part of the system by design (for example, a newer service and an older component), keep the team together. (See Chapter 8 for more on patterns for long-term “continuity of care” for older software systems.)

Sometimes, two or more teams may feel the need to communicate on software purely because the code for their parts of the system is in the same version-control repository or is even part of the same application or service, whereas logically, it should be separate. In these cases, we need to use “fracture plane” patterns (which will be discussed in Chapter 6) to split up the software into smaller chunks that can live in separate repositories.”

First, from user interaction design we actually look for these things, I saw a wonderful picture of a park as an illustration once. I couldn’t find it so this will do.

The idea is that “unintended uses” reveal real needs. So if I saw that two teams, that according to my architecture drawing shouldn’t need to collaborate, were talking a lot, I would definitely be interested, but for the opposite reason: They have clearly discovered something that is not well understood. At least by me.

Optimal UX design would wait for some of these patterns to emerge, and then “pave” them, by making them easier to use, helping the users avoid some of the hacks they are currently employing to Get Shit Done.

This is not a bug, this is a feature. Teams that reach out and collaborate when needed are the absolute best.

This is not a flaw in the teams, this is, if anything, a flaw in the architecture drawing. Which to be honest is mostly garbage anyway.

The first line is yet another misunderstanding of Conway:

“One key implication of Conway’s law is that not all communication and collaboration is good.”

However, I feel we have covered that enough already.

The fascinating thing is that it feels like they constantly draw the opposite conclusion from me based on the same information, for example: “We need to look for unexpected communication and address the cause”. If the continuation of this was: “so that we can figure out how the current architecture is not serving us well and figure out how we can improve it”, I’d be on board, it’s a bit Big Brother, but it’s fine, I guess. But no.

“A simple way to restrict communication is to move two teams to different parts of the office, different floors, or even different buildings.”

Imagine being such a control freak that you move a team to another building to stop them talking to each other.

“Sometimes, two or more teams may feel the need to communicate on software purely because the code for their parts of the system is in the same version-control repository […]. In these cases, we need […] to split up the software into smaller chunks that can live in separate repositories.”

Don’t tell Google or Microsoft or Linux or any browser or compiler or…

God forbid y’all even share a CI, y’all might speak to each other!!! One git repo per person I say, people talk too much already. Hire an integration manager to figure this shit out, my door is locked and my slack is offline.

Anyway, that is the whole ideological basis of this entire book and all its associated reorg consultancy operation:

People talk too fucking much, it’s fucking with my architecture drawing.

Got a chat platform like Slack or Teams or whatever? A way for people to talk to other people across process boundaries gasp? Beware:

“this kind of many-to-many communication will tend to produce monolithic, tangled, highly coupled, interdependent systems that do not support fast flow.”

Past Patricia was on the money:

“I posit that this book is a result of a bunch of folks who are personally struggling to understand how anything is ever built by anyone.” 12

An aside, but in my experience if you want to make a great API you need a lot of collaboration with users of that API.

I’m back. Chapter 2 didn’t really bring anything more to the table except ending with a subsection of This Reorg Is Different, It’s The Other Reorgs That Are Bad. Also the Spotify stuff made its entry. And these need to be studied because they seem to be pivotal to this whole book.

- Kniberg, Henrik, and Anders Ivarsson. “Scaling Agile ® Spotify with Tribes, Squads, Chapters & Guilds.” Crisp’s Blog. October 2012. 13

- Kniberg, Henrik. “Real-Life Agile Scaling®” Presented at the Agile Tour Bangkok, Thailand, November 21, 2015. 14

- Kniberg, Henrik. “Squad Health Check Model-Visualizing What to Improve.” Spotify Labs (blog), September 16, 2014. 15

One of the important things about this whole idea from Spotify is right there in the title and involves a problem most organizations don’t have: hyperscaling of an organization while maintaining a product that is in production.

This problem means that one will need to figure out the tradeoffs one needs to make for the organization not to grind to a halt when scaling the number of people by some factor every year. To be honest I can’t imagine even a 50% increase in a year not being an issue in an engineering organization.

I think this is important to discuss because it is central to this entire class of problems. What happens to an engineering org that increases by 100% in a year, that has to onboard all of these people, teach them, show them the ropes, mentor them, help them?

We know that onboarding people is time consuming, and that time is taken from the people who are already experienced in the org. Unfortunately these are the people keeping your product running.

So by upping your headcount you will probably slow your organization down. When you up by a lot, you might grind it to a halt. Which reminds me of this clip from Bad Boys 2:

”- Carlos, this is a stupid fucking problem to have, but it is a problem, nonetheless,” the drug kingpin says while shooting at the rats eating his money 16

So what do you do if company leadership has decided that this is a good idea? Hyper Scaling FTW!!!

- You have to protect the product, you can’t let loose a horde of people who have no idea what they are doing, the product will go to shit

- You have to get these people productive

- You can’t afford to spare all the people this onboarding would require

This is not normal, nor is it advisable. It is mostly a massive waste of money. Because you can’t afford to spare all the people you’d need to do this responsibly. So instead you have to do it in a way where The Horde doesn’t stampede the people keeping the product running.

Now imagine that this is your situation (again, not at all normal or wise), in such a situation building a wall between Current Teams and The Hoard makes sense. And The Hoard will have to absorb itself. You’ll have someone who’s been there for 2 months training someone who just started. Teams do whatever, but off to the side. No one is keeping tabs on everything that is being made, you’re just doing your best to make sure The Hoard doesn’t break anything important. And the best way to do that is to say they are greenfield. “Go make new thing!”

And from what I heard that was what happened at Spotify. Multiple distributed teams came up with the same idea and ran with it, multiple concurrent completely independent implementations of the same idea happened. Lots of stuff was thrown away. But Spotify survived as a product.

This isn’t good engineering.

This is a complete waste of money and talent.

Hyper scaling an engineering org is a Bad Idea Actually.

But if it happens, if it’s out of your hands, you do your best to protect the product, because the product is what is paying for all of this shit.

Fast forward to 2015, the title of the talk is still about trying to do agile while scaling “Real-life Agile Scaling” 14, trying to balance autonomy with someone having a plan. And again they are reaching for the solution for the problem of Hyper Growth: You need to protect the people doing the work that is paying for all of this shit.

In my clearly not so humble opinion the “Spotify Model” is Bad Practice for basically any org that is not a startup that is hyper scaling it’s engineering org: WHICH YOU SHOULD NEVER DO.

To quote the drug kingpin again: “This is a stupid fucking problem to have” 16

This is expensive and produces results that you could’ve gotten done better with a much smaller organization.

The problem is the hyper-growth.

You can’t absorb it responsibly.

So you have to do hacks to not grind to a halt.

And one of those hacks is to build walls.

But those walls produce a whole host of other problems.

That’s all I’ll say about Spotify. Let’s move on.

Ok, one last thing on Spotify, because I don’t want people to think that whatever they did was bad. They tried to solve a problem that is known to be really hard. I am not criticizing the engineering leadership here, maybe this was as optimal as anything can get under these circumstances and Spotify is still around and to be honest that’s the proof in the pudding here.

What I am saying is that if you don’t have this particular problem, this solution is not for you. This solution is Bad Actually in any regular situation. It creates a lot of walls and lack of communication which will cause a lack of feedback and probably will result in a lot of do-overs and stuff that gets thrown out. And not shipping is killer for morale.

You’ll become less productive than you could’ve been for no good reason.

I realized today that it was very unfortunate for the authors that I am the person reading this book, because I have actually read a lot of (most of?) the stuff they are referencing, and also I’ve been shipping shit for 20 years. I can actually build stuff and I’ve done that in companies ranging in size from 2 people to 40.000 people. In programming languages from TypeScript to assembly.

Like the Team of Teams book which I read years ago, and what I remember from that is that it’s about a military version of servant leadership, that you need to trust your people because they are the ones who are in it, they are the people who know best. And you need to get out of their way, give them what they need and trust their judgment. It’s not about stopping them communicating with other people.

I worry that they have a lot of cherry picking of quotes out of context presented as if these sources agree with them. Just like the whole Conway thing, on which this whole book rests.

Remember how I said that a massive chunk of the book is regurgitating (badly) Other People’s Thoughts? I will prove it. Just give me a minute.

Ok, this is petty, but I had to read it twice so…

A regular full book page is approximately Times New Roman 15, and a references page is approximately Times New Roman 12. The content section of the book is 185 pages, but if we subtract blank pages, summaries and pictures it’s approximately (generously) 150 pages. The reference section is 12 pages in a much smaller font. If the references pages had had the same font size as the rest then it would be approximately 20 pages coming in at around 13% of the number of pages that the main content has.

Each main content page had 38 lines. So approximately total 38*150 lines = 5700.

There are approximately 20 refs per page, 12 ref pages. So if we assume each reference is on average 5 lines in the book, then we have 1 200 lines that are other people’s words.

That means that 21% of the book is other people’s words.

It feels like a lot more to be honest. But tbf a lot of these works are quoted multiple times, so it just might be.

Ok, ok, we need to speed up this shit.

Chapter 3: “Team-First Thinking”

Starting chapter 3 which is the last in part 1 which is the important part of this book. Because part 1 is where they lay out Why This Is A Good Idea Actually.

We start with a typical (for this book) “logical” reasoning: Dunbar’s number says we can only trust 5 people deeply, psychological safety* concludes that trust is critical for team excellence**, therefore team excellence requires a team size of 5-9 people. Why 9? Because Amazon and something about 2 pizzas.

** Dunbar talked about social connections (extrapolated from brain size (wat?)) not about work colleagues. His methodology is highly contested. But if true this would probably be your family.

*** they don’t actually say “psychological safety”, which was developed by dr. Amy C. Edmondson, whose original research was on medical teams, they don’t mention her or the term, but refer to it through referencing a blog post about google teams. Which makes sense when you know that Google “discovered” dr. Edmondson’s research after they failed to explain team excellence in Project Aristotle. (Y’all I told ya, I did the reading)

** that’s not really accurate because what dr. Edmondson found was that trust fostered an environment where people were not afraid to speak their minds and this made team learning possible, it was the team learning that produced excellence. But whatever.

I think this is a perfect example of how the entire book is. They mischaracterize a bunch of completely different sources of research to conclude what they want to conclude: Amazon rocks, right?

I’m not saying anything about what is or is not a perfect team size, I’m sure everyone has a gut feeling about that, what irks me is this fake “logical conclusion”. And here in particular it annoys me that they erased a woman who pioneered a whole new understanding of groups of people making each other better.

Dr. Edmondson’s research is extremely interesting, especially because she started off designing a metric for excellence in medical teams, and when she had collected the data it showed a strong correlation in the opposite direction of her thesis, making her have to dig deep into what was actually happening. No spoilers, it’s really good. 10/10 do recommend.

They go on to say that: actually there is a lot of research pointing in all sorts of directions on team size, but team size correlates with trust and trust equals team excellence, which they have actually not shown, but they now state as a fact.

In my recollection Dr. Edmondson didn’t talk about team size, what she focused on was team culture. How we treat each other was key, not the size of the team. I find this entire argument extremely weak and misses completely the central point in her research. But I guess that’s understandable since they have completely erased her from the narrative.

Their actual argument is “Amazon says 2 pizzas, and Amazon is cool” also by the time we reach the bullet point version of the previous text, but before we reach the picture of the previous text**, the team size is now 5-8, not sure what happened to that last person.

** This is also very tiresome, but I assume it’s down to the American rule of “Tell them what you’re going to tell them, tell them, tell them what you told them”. Unfortunately, we will be told a fourth time in the chapter key takeaways and a fifth time in the “TIP” box.

Note also that yet again our “stable and long running teams” might need to be split up if they exceed this magical number which is based on the highly disputed “Dunbar’s Number” (which wouldn’t apply anyway, because it would be your family and friends) which an anthropologist made up 30 years ago and extrapolated from the brain size of primates.

But whatever.

I have thoughts on this, but for now I just want to show this dynamic in the text (see pic). Here they use the work of 3 widely different “thought leaders” to conclude you shouldn’t add new people to a team.

“Work Flows to Long-Lived Teams

Teams take time to form and be effective. Typically, a team can take from two weeks to three months or more to become a cohesive unit. When (or if) a team reaches that special state, it can be many times more effective than individuals alone. If it takes three months for a team to become highly effective, we need to provide stability around and within the team to allow them to reach that level.

There is little value in reassigning people to different teams after a six-month project where the team has just begun to perform well. As Fred Brooks points out in his classic book The Mythical Man-Month, adding new people to a team doesn’t immediately increase its capacity (this became known as Brooks’s law). In fact, it quite possibly reduces capacity during an initial stage. There’s a ramp-up period necessary to bring people up to speed, but the communication lines inside the team also increase significantly with every new member.

Not only that, but there is an emotional adaptation required both from new and old team members in order to understand and accommodate each other’s points of view and work habits (the “storming” stage of Tuckman’s team-development model).

The best approach to team lifespans is to keep the team stable and “flow the work to the team,” as Allan Kelly says in his 2018 book Project Myopia.”

“Long” running teams

ROFL, do you want to know the length they mean by “long running”?

- Low end :9 months

- Norm: 18 ?

- High end: 24 months

Jesus Christ, people aren’t fully productive in most domains/codebases before they’ve been doing it for 6 months to a year in my experience. Though I’m sure senior people can do it faster, especially with simpler systems/domains.

If you’re switching people out as fast as this, you are losing a massive amount of institutional knowledge.

I was assuming 4-5 years. Silly me.

By the way, 2 years? This is not “long running” in any company I’ve been in. This is on the low end of normal.

I hate that I have actually read these books they bring up.

This debate technique of just flooding every statement with references to 5 different books makes it impossible for anyone who doesn’t read a whole shit ton of books on the topic to refute anything. Who will bother to read 5 books to say: “Well, actually”?

In my defence I read the books on my own accord before this book.

Skipping past obvious points:

- People should maintain what they build

- Diversity is good actually

- Lift up the whole team, not individuals

And also stuff that’s boring to debate:

- Should there be code ownership or nah

- What makes a good team member

“Cognitive Load”

Getting to one of their core concepts “Cognitive Load”

New plan: fold laundry while listening to the audiobook, and occasionally peeking at the physical book. My brain keeps trying to run away. Must persist.

Btw, when I say skipping past I don’t mean I don’t read it, I mean I can’t be bothered to discuss it.

OMG. I missed this in my first reading: THEY DID NOT INVENT COGNITIVE LOAD.

This is Yet Another: Other Persons Thought

Jesus Christ.

Shout out to psychologist John Sweller whose 1988 work I’ve apparently missed out on: “Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning” 17

Brain decides to digress to read said paper.

This is an interesting paper (not done reading), basically it seems to be about the difference in how juniors and seniors approach problems, where seniors tend to “recognize” a problem as belonging to a certain category and that they tend to categorize problems according to their method of solution. (Continues to read)

Ok, so the mechanism being studied is how one goes from being a junior to a senior (“schema acquisition”, “schema” being a pattern for recognizing a problem).

Oh my, he seems to be making a massive assumption:

A problem solving computer program will exhibit the same characteristics as a human solving a problem.

“Programs which model problem solving using means-ends or alternatively, nonspecific goal strategies can be analyzed in order to obtain an indicator of the relative information-processing capacity required by the two strategies. This section describes such a procedure.”

Ok, let him cook, as the kids say.

Oh my, this is a contradiction to his previous statement about studies of experts:

“It seems plausible to suggest that the more productions that need to be considered at each step in the problem and the more statements that need to be matched in order to decide between productions, the greater is the “cognitive load.””

Seniors don’t remember “more things” they remember “bigger things”:

“Chase and Simon (1973a, 1973b) found that while both novices and masters remembered both realistic chess configurations and sequences of moves in chunks, the number of chunks did not differ appreciably. Differences did occur in chunk size with masters’ chunks being far larger than those of novices.”

It’s not about thinking faster, it’s about remembering bigger.

Ok, this got boring and more than a little circular. They had one or more programmers create a program that is supposed to simulate problem solving and they didn’t ask them how they solved the problem of creating that program?

As far as I can tell this paper says: if you don’t know anything except basic knowledge of “operators” (I think a programming language would qualify as a set of operators) and have no tools to help you or colleagues, then the simpler the problem the easier it is.

This is a completely unrealistic scenario (and also uninteresting conclusion) and also doesn’t apply. You don’t need to know how to implement merge sort to call sort() on an array. We use abstractions, libraries etc to reason at a higher level, but the computer still needs to do all the things in the libraries etc.

This whole paper is silly. People don’t solve problems like this. We abstract into chunks (like the reference earlier) example from chess: “an opening”, example from programming: “a database” or “sort()” or “type”.

Basically he’s concluding that randomly searching for a solution is less work than actually designing a solution. I mean yeah, I call that “randomly throwing things at the wall and seeing what sticks”, that’s not optimal problem solving, that’s being clueless and at your wits end.

Can you imagine reading a paper on “being clueless is good actually” and going YES!!! ON THIS I WILL WRITE MY BOOK!!!

Speaking of, back to the book, this was a disappointment.

ROFL. They didn’t read the paper. They read Someone Else’s Thoughts on the matter 🤣

Shout out to Jo Pearce, I guess.

Omg. The references to Pearce are a link to a slide deck and a blog post. 💀 Hashtag doing science

- Pearce, Jo. “Day 3: Managing Cognitive Load for Team Learning.” 12 Devs of Xmas (blog), December 28, 2015. 18

- Pearce, Jo. “Hacking Your Head: Managing Information Overload (Extended). SlideShare, posted by Jo Pearce, April 29, 2016. 19

Holy fucking shit, this goes on for 20 pages, I need moar laundry.

As a surprise to absolutely no one we are yet again splitting up a so-called “long running team”** now because they have more than one “complex domain”. What a domain is is still a bit nebulous, because it doesn’t seem to be in the Domain Driven Design or Domain Expert sense.

Whatever. Split away.

** I have a sneaking suspicion that the “long running team” guarantee only happens after One More Re-org For The Road.

Jesus Christ. Is your team overwhelmed by tasks you keep on heaping on the same set of shoulders??

COGNITIVE LOAD

Team API

They are literally using the words “team API”.

Broke: talking to people

Woke: reading the docs written by the person next to you

Bespoke: submitting a jira to the person sitting next to you saying the docs were unclear

Apparently pairing with people on other teams or participating in “communities of practice” etc are not affected by the “conways law banning communication” because suddenly talking is good when… something?

Turns out Robert Axelrod** and Mark Burgess*** found that knowing people in other teams is Good Actually? Bombshell. Or as the book calls it: “groundbreaking”.

Imagine. Talking To People Might Be Good Actually?

** Axelrod, Complexity of Cooperation

*** Burgess, Thinking in Promises

Good thing we didn’t spend more than half a page on that, don’t want to encourage that kind of behavior.

The rest of chapter 3 is a bunch of “case studies” of physical configurations of office space written by people in those organizations. They mostly contradict everything said so far in the book. This is not discussed at all.

Part II: “Team Topologies that work for flow”

Chapter 4: “Static team topologies”

On to part 2 “Team Topologies that work for flow” and chapter 4: “Static team topologies”

Note that flow, stream and domain have not been properly defined yet. And cognitive load seems to be anything that makes you unhappy at work.

“Text book” and Other People’s Thoughts

The Spotify blog post made another appearance. (This is maybe the fourth time so far in the book).

7 pages into the chapter and nothing has been said beyond “DevOps happened”

A lot of stuff being said about teams that I find very shallow, but deep analysis is not a strong suit for this book.

Product Management has entered the chat

We’re just doing a long list of practices at the moment. This is the “text book” feel I talked about before.

-

As ops moved to cloud (and became Platform) and because of what was learned from DevOps: they have to create self service infrastructure

-

For self service infrastructure developer experience is important

Yes, and? Because this is not their work, this is just listing up common industry practice.

Maybe we can discuss some of the problems we have seen with this? That would maybe be interesting?

This chapter is boring. We are now at SREs are a thing, they have them at Google.

This is what I mean about “textbook style”, this is just regurgitating (10 year old) common knowledge, this isn’t bringing anything new, this is not their work. It belongs in a textbook for a college course or something. This book is not such a book. Or I really fucking hope not.

“Technical and Cultural Maturity

Organizations at different stages of technical and cultural maturity will find different team structures to be effective. For example, by 2013, both Amazon and Netflix had a well-established strategy, using cross-functional teams with end-to-end responsibility for the services they provided to the rest of the organization. Meanwhile, traditional organizations adopting Agile- moving to smaller batches of delivery-often lacked the mature engineering practices required to keep a sustainable pace over time (such as automated testing, deployment, or monitoring). They could benefit from a temporary DevOps team with battletested engineers to bring in expertise and, more importantly, bring teams together by collaborating on shared practices and tools.

However, without a clear mission and expiration date for such a DevOps team, it’s easy to cross the thin line between this pattern and the corresponding anti-pattern of yet another silo (DevOps team) with compartmentalized knowledge (such as configuration management, monitoring, deployment strategies, and others) in the organization.”

They keep on bringing up DBAs and does your org actually have people with DBA as their work title today?

Agile coaching is a hell of a racket. Get an org to buy hundreds or thousands of copies of your book and then charge them for training and coaching on top of that. I should write a book, this sounds profitable.

Spotify enters the chat. Again. No idea what number we’re at now.

Chapter 4 was 100% Other People’s Thoughts. Absolutely no original thought.

Chapter 5: “The Four Fundamental Team Topologies”

Moving on to chapter 5 “The Four Fundamental Team Topologies”

I have discovered a hack! Look at the reference section for this chapter, and from this we can tell that this will be a lot of Amazon Is Amazing, Platform Teams!, Agile! and of course: ✨ this chapter’s dose of the Spotify blog posts ✨

Chapter 5 page 1.

Book: Do we have the right teams in place?

Me: you know you can ask them, right?

Book: Are we lacking capabilities in some areas that are not being addressed by any team?

Me: Asking them sounds like a good idea.

Book: Does it look like teams have the necessary balance between autonomy and support by other teams?

Me: HOLY FUCKING SHIT JUST FUCKING ASK THEM JESUS CHRIST YOU’RE FUCKING KILLING ME

Book: To answer this question we will reorg the organization

Me: fucking kill me now

Four team topologies

In case you were wondering: “these are the only four team topologies needed to build and run modern software systems”

What is a “topology” you may be wondering as we enter chapter 5.

It’s a term for “team type”.

It’s just a team.

Forget math. It has nothing to do with math or maps or anything. The book could actually be called “Team Types” but I’m sure that’s bad for marketing.

Also we still don’t know what “stream” is but if I recall correctly it is related to “flow” which if I recall correctly led to one of my favorite quotes from last time.

- Stream-aligned team

- Enabling team

- Complicated-subsystem team

- Platform team

DRUMROLL!

“A “stream” is the continuous flow of work aligned to a business domain or organizational capability. Continuous flow requires clarity of purpose and responsibility so that multiple teams can coexist, each with their own flow of work.

A stream-aligned team is a team aligned to a single, valuable stream of work; this might be a single product or service, a single set of features, a single user journey, or a single user persona.”

We are at 2 or 3 of Amazon Rocks Actually. Whatever they did 15 years ago is awesome.

YASS! “A stream should flow unimpeded”!!! This is my favorite. Absolute meaningless garbage that is perfect for a motivational poster, with an IKEA style picture of a river. Love it.

Enabling Team

“Enabling Team” is basically a “DevOps team” (which they hated on last chapter but who remembers that anyway) but now you can do that same thing for All The Things. I’m not saying it’s bad, just rolling my eyes at making up yet another word. But ok fine. You can have “Enabling Team”. It’s fine. 🤷🏻♀️

Other People’s Thought: CapEx vs OpEx

Here is an excellent example of Other People’s Thoughts. This is imo a very important observation that many MBA type folks fail to internalize: how you finance stuff actually has an effect on how the work is done. And you can’t optimize one budget at a time, because a 1000$ savings on pencils can be a 100,000$ cost on dev time. Stop thinking you know what the effects are and start fucking talking to people.

The below are the words of a couple of people at Auto Trader in the UK:

“To make things worse, before us new software-development projects were financed with capital expenditure (CapEx) but the IT operations activities were treated as operational expenditure (OpEx,) which produced a sharp divide between teams building things and teams running things. Software development (Dev) time was booked 90% to CapEx; effectively, they were told, “You must build new things.” They could not work on fixes or things that were right for the customer. Dev was working to serve the “boss” of product management rather than users of the services. We knew we had to change this.

So in 2013, we moved everyone to OpEx. Now everyone is simply doing the work needed to make the company money. With our OpEx-only model, everyone is closer to the customer because we are not thinking about “building new stuff for the product manager” but meeting the needs of users. In fact, OpEx is a deliberate enabling constraint for us: we have a stable workforce of around eight hundred people, and we have no plans to grow hugely. This stable set of people helps with the continuity of care for our software applications and services.”

Good news! We are over halfway through the book!

Page 100!

The only new thought so far in chapter 5 is Enabling Teams, I don’t know if they came up with it or if they just re-named something someone else came up with. This addresses a real loss that happens when going to “feature teams”/”cross functional teams”, you often lose this depth of knowledge and time to help. And no, Community of Practice is not enough to replace it, it is a real loss of institutional knowledge and capability. So maybe Enabling Teams are worth a shot for some orgs?

I am not incapable of saying something good, but after the Cognitive Load thing I’m suspicious of everything.

Before I wrap up for the night I want to add one last thing: an organizational model that works for a webapp might not work for a company that builds a physical device like a switch or a drone, or an org that writes software to regulate a dam or the electrical grid.

It is extremely simplistic and condescending to think you can show up and tell folks how to do their craft when you don’t know shit about their context or domain.

Thinking you can is imo proof that you can’t.

We are a young profession, we don’t know how to do this well. We’re trying, but we’re also extremely susceptible to cargo cults and seemingly quick fixes. We are notoriously bad at seeing what we make worse by potentially making other things better. We are extremely sure of ourselves while we have a proven track record of fucking up on a global scale.

What our industry needs is a whole lot more listening and humility, and a lot less telling people (whose job you couldn’t do to save your life) how to do their job.

Platform architecture

Y’all ready to finish this book?

We are about to start the “Platform architecture” part of chapter 5 which is not my specialty, but people have told me it is problematic. If you are a platform engineer feel free to educate me on this part.

Pile of laundry to get my brain to not chicken out.

I’m starting to feel bad for Henrik Kniberg, author of the “Real Life Agile Scaling” slideset and associated blogposts, otherwise collectively known in this thread as the “Spotify blog post” (it’s two blog posts and a slide set) other places known as “The Spotify Model”.

Here he is again in the very first sentence. The authors are obsessed with this 10+ year old work that Spotify has tried to distance itself from for a decade 20.

1/2 a page on Thinnest Viable Platform, which is basically “don’t overengineer”? Ok, I guess.

“The Thinnest Viable Platform

The simplest platform is purely a list on a wiki page of underlying components or services used by consuming software. If those underlying components and services always work reliably, then there is no need for a full-time platform team. However, as the underlying substrate becomes more complicated — even if all components and services are still outsourced-a platform team can provide a valuable management abstraction over the details of the platform, dealing with the coordination of new and deprecated APIs and components. If an organization needs to build custom solutions and integrations into the platform to meet the needs of Dev teams, then the activities of the platform team increase in scope further.

In all cases, we should aim for a thinnest viable platform (TVP) and avoid letting the platform dominate the discourse. As Allan Kelly says, “software developers love building platforms and, without strong product management input, will create a bigger platform than needed.” A TVP is a careful balance between keeping the platform small and ensuring that the platform is helping to accelerate and simplify software delivery for teams building on the platform.”

Ok, this was so basic I doubt it would be useful to anyone working on platforms. This sounds like an executive summary for managers…

WAIT. HOLD THE FUCKING PHONE.

THAT’S WHAT THIS FUCKING BOOK IS!!

IT’S A FUCKING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FOR MANAGEMENT THAT KNOWS FUCK ALL ABOUT TECH ORGS!!!

This is a Tech Orgs For Dummies book!

Here is a description of a relatively normal tech org for a webapp, plus let’s spice it up with not letting people talk to each other!!!

Sell books, sell consulting, do so many reorgs and PROFIT!

The rest of chapter 5 is just reorg.

Chapter 6: “Choose Team-First Boundaries”

Alright! Chapter 6!

“Choose Team-First Boundaries” based on the references I’m guessing it’s about DevOps.

“Monolith Bad”

Sigh. We’re on the “monolith bad” “DBA bad” train. I promise you a DBA hurt these people.

Is there a book on Minimal Viable Architecture? There should be and these people should read it.

MICRO SERVICE ALL THE THINGS!

CHOP UP THAT MONOLITH!

WHAT IS A MONOLITH?

EVERYTHING I DON’T LIKE

Lol, I’m gonna do their quote out of context cherry picking back at them:

“Monolithic thinking is “one size fits all” thinking for teams that lead to unnecessary restrictions” (context skipped to make it seem that they agree with me)

It hadn’t occurred to me that this was a whirlwind tour of “relatively new” practices for bog standard webapp producing orgs, plus some destructive communication restrictions.

Now that it has, I’m also pissed at the intended audience of this book. If this is the level of effort you are willing to put in to try to understand the sector you’re in, you are in my absolutely not humble opinion: completely unqualified to manage such an organization.

Jesus Christ, most of the people who work for you are VASTLY more knowledgeable than this and YOU are going to tell THEM how to do THEIR job?

WTF. Seriously?

Just fucking ask them what they need.

You know what is hilarious? They want to get rid of architects because architecture needs to be evolved by the teams, BUT this whole book is about doing Top Down Up Front architecture through the most invasive means possible: by fucking up all the teams and collaboration in an org.

And this “architecting” activity is done by people who are so clueless about dev orgs they find this book insightful.

It is fascinating how little self awareness is expressed in this book.

How do you write multiple paragraphs on how architecture needs to evolve more or less organically as we learn and understand more about the domain and the users and their needs, while at the same time writing a whole book on how YOU as a complete outsider to an org, its domain and its organization, can rearchitect (in the shape of a reorg) everything?

The Dunning-Kruger** is stunning

** which is also highly disputed and probably completely misused/wrong, but in that way fitting right in in the context of this Gish Gallop*** of a book.

*** “Gish gallop is a rhetorical technique in which a person in a debate attempts to overwhelm an opponent by presenting an excessive number of arguments, without regard for their accuracy or strength, with a rapidity that makes it impossible for the opponent to address them in the time available.” 21

“In the book Designing Autonomous Teams and Services, DDD experts Nick Tune and Scott Millett give an example of an online music-streaming service with three subdomains that align well to business areas: media discovery (finding new music), media delivery (streaming to listeners), and licensing (rights management, royalty payments, etc.).

Identifying bounded contexts requires a fair amount of business knowledge and technical expertise, so it’s normal to make mistakes initially. But that should not deter you from improving and adapting as you understand your context better, even if that involves some kind of recurring “cost” of service redesign. There is often some level of semantic coupling in our design whereby, in the words of Michael Nygard, “a concept may appear to be atomic just because we have a single word to cover it. Look hard enough and you will find seams where you can fracture that concept

In other words, a piece-meal type of evolution is expected when breaking down systems by bounded context.

Other advantages of applying DDD include focusing on core complexity and opportunities within a bounded context for a given business domain, exploring models via collaboration between business experts (because there are now smaller domains to think about), building software that expresses these models explicitly, and having both business owners and technologists speaking an ubiquitous language within a bounded context.

In summary, the business domain fracture plane aligns technology with business and reduces mismatches in terminology and “lost in translation” issues, improving the flow of changes and reducing rework.”

I’m bored, chapter 6 is 100% about splitting up code to fit with whatever the person who reads this book feels makes sense.

Key concept: Fracture plane

Moar “Cognitive Load”

“Cognitive Load” pisses me off as much as it did the first time, but this time it’s actually a bit worse because I read the bullshit paper they got it from.

Tell me more about how you have no fucking clue what you are talking about you condescending pencil pusher.

What the actual fuck is this garbage? An org that maintains and ships embedded devices, with apps to control them and a fucking cloud backend, and you come in with:

Writing code from bootloaders to iOS/Android apps to cloud to probably a webapp introduces “cognitive load” if you have to do it end to end? And this is a fucking “technical limitation”?

Jesus Christ get off your fucking phone, it’s an embedded device with apps and a cloud backend with a web interface.

Holy shit. This is so fundamentally ignorant I am at a loss for words.

“Real-World Example: Manufacturing

When we talked about technology as a fracture plane, we stressed how this should be applied sparsely and mostly for older technology that feels and behaves considerably different from modern software stacks. Inevitably, you will find exceptions. The difficulty is understanding when an exception is valid and when an easy way to make quick progress ultimately limits effectiveness.

To illustrate, let’s look at a scenario that we found at a rather large manufacturing client we worked for. This large manufacturing company produces physical devices for consumers. All the devices are equipped with loT capabilities, including remote control from a mobile app and remote software updates via the cloud. Devices are controlled from both the cloud (via scheduled activity) and by interactive user control (using the mobile app). All activity logs and product data are sent to the cloud, where they are processed, filtered, and stored.

It would be extremely challenging for a stream-aligned team to own this entire end-to-end user experience - mobile app, cloud processing, and embedded software for the device-given the size and cognitive-load limitations highlighted early in the book. Making end-to-end changes across three very different tech stacks (embedded, cloud, and mobile) requires a skill mix that is hard to find, and the associated cognitive load and context switching would be untenable. At best, changes would be suboptimal in technical and architectural terms; at worst, they would be fragile, lead to steadily increasing technical debt, and possibly provide a poor user experience for customers overall.

Instead, by accepting the technical limitations of the system, teams could be organized along the natural technology boundaries (an embedded team, a cloud team, and possibly, a mobile team). The gap between these technologies (in terms of skills and speed of deployment) imposes a different pace of change for each, which is the key driver for separate teams.”

People pay these people actual money.

That’s the end of chapter 6 and part 2, bringing us the what I expect to actually be the worst part of the book:

Part III: “Evolving Team Interactions for Innovation and Rapid Delivery”

Chapter 7: “Team Interaction Modes”

Ref the post a couple of posts up, in case it wasn’t clear: that org is doing amazing work and should not be paying these people for anything.

I got so annoyed I lost the cap of my yellow highlighter.

This chapter is just garbage because it displays a complete lack of understanding of how stuff that people actually use, is built.

If you want people to use what you build you have 2 basic options:

- Give them no other option. Examples: your company’s intranet (which are almost always absolute garbage) or whatever system they need to use to do their fucking job. In both cases you literally pay them to use it.

- Make it useful and/or fun.

Unfortunately for this fucking book, there is a lower bound to how garbage your product can be, and still qualify for 1. So how do you figure out what your users need and how it is to use your stuff: YOU NEED TO FUCKING TALK TO PEOPLE.

- Oh I don’t have to talk to people, I have an API

DUDE, THE USERS OF YOUR FUCKING API AND YOUR X AS A SERVICE ARE YOUR FUCKING USERS. YOU HAVE TO TALK TO THEM. ALL THE FUCKING TIME.

Fracture all the planes you want, you are just creating MORE FUCKING PEOPLE TO TALK TO.

DevEx and UX don’t happen in a vacuum. This is fucking delusional.

I have a talk about this in the morning. I need a whole week. 😭😭😭

I’m rolling my eyes through chapter 7 as fast as I possibly can. This whole chapter should be deleted.

Ok, I feel I need to be clear here. My problem with this chapter and to be honest the whole book is that you can’t sit on the outside and divine these things.

The people know what they need.

And they don’t need you to tell them that they are now allowed a “collaborative interaction mode” (just this once as a treat) because they are figuring out an interface.

Dude. These are grown ass professionals. They know how to do their fucking jobs.

This book is what mansplaining would look like if it was published as a book.

Chapter 8: “Evolve Team Structures with Organizational Sensing”

Final chapter (before the conclusion!)

Chapter 8: “Evolve Team Structures with Organizational Sensing”

Based on the references I’m gonna guess it’s about Agile! and maybe kubernetes?

One of the things that makes this book so frustrating is that they are constantly saying things that are contradictory, but without any reflection on those contradictions.

Shit is complicated, and it always depends, trust me I know.

But that is also the reason why you have to discuss and reflect, so that you know what you should take into consideration when deciding on a path forward and also what is the smallest experiment you can make to figure out if this is All A Massive Mistake Actually.

You cannot with a straight face quote Accelerate (great book) which states as a positive (!) that “architecture and teams are loosely coupled” when YOUR ENTIRE FUCKING BOOK IS SAYING THE FUCKING OPPOSITE AND WEAPONIZES IT TO IT’S ABSOLUTE FULLEST EXTENT.

Come on.

You don’t win by saying all the fucking things.

It’s less than zero, it’s zero, it’s more than zero. Look at me! I’m smart.

Zero knowledge of products outside of webapps

Yet another example of not understanding the technologies they talk about: they are talking about cloud devs and embedded devs as being worlds apart. This is ridiculous. These two groups share a lot of tech, concepts, tools, programming languages and mental models. It should be a breeze for them to collaborate.

I don’t expect people to know that, but the devs would know that after a short 30 minute presentation.

You can’t re-org / re-architect shit you don’t understand.

This is infantilizing people with deep expertise THAT YOU DON’T HAVE.

Physically moving people to stop them communicating

How much of a micro-managing control-freak do you need to be to think that this is ok for you to decide?

“There might be times when there is a need to colocate people - at the same desks or simply on the same floor in the same building - to produce the kind of proximity that encourages the right amount of collaboration. At other times, teams might move to separate floors or even separate buildings in order to help enforce an API boundary”

Stay in your fucking lane, and let people do their jobs.

Let people talk when they need to talk. They should not need your permission or even knowledge.

Kubernetes for teams: Cybernetics

OMG. Yet another thing I missed the first time I read the book. Maybe because I hadn’t read “The Unaccountability Machine” 22 yet.

In the subsection “Self Steer Design and Development” they bring up Cybernetics. Cybernetics is based on the same Greek word as Kubernetes and is actually where Kubernetes took its name!

Cybernetics is a broad and quite old field that spawned a lot of subfields in computer science, like compression (yeah, random).

Anyway, in cybernetics you are modeling/creating a complex adaptive system. It has some sort of central controller that monitors the health of all of the things in the system (which emit feedback) and this central component can then regulate the system through various mechanisms.

TL;DR: it’s Kubernetes.

They are literally going to do Kubernetes on teams.

Me: I’m dying. My liveliness check is failing. Help.

Kubernetes: ok. kill -9 patricia

Me: SIGKILL ☠️

My jokes were apparently not niche enough yet.

JUST ASK THEM.

I’M DYING HERE.

I am an introvert, like at least half my field, but I know from 20 years of professional experience building shit with 1 to tens (hundreds?) of millions of users:

YOU HAVE TO FUCKING TALK TO PEOPLE.

Only juniors think this is a profession that is solved at a keyboard all by yourself. Not talking to people is 💯 junior behavior.

When you’re a junior you’re focused on building your technical skills, when you’re a senior you focus on Building Useful Shit That People Will Use.

I told you 23 some DBA hurt them. Step forward, what did you do? Did you show them the Oracle bill? You know that’s not allowed. We will let Patricia “refactor” your stored procedures as your punishment.

Alright, 2 things:

- The authors really need to read about Dr. Amy Edmondson’s work on her doctoral thesis. Then they would understand feedback much better than this.

- People don’t “develop” empathy. The normal mechanism is: we empathize with the people we know. Do you want people to “empathize” with their users? Then they need to get to know them, talk to them face-to-face, observe how they use the product in real life.